|

| |

Why Teams?

The current

increase in the use of teams reflects changes in the competitive environment of

many organizations. Organizations

are experiencing dramatically increased pressures for performance.

They are being required to develop and deliver products and services at

lower costs but with higher quality and increased speed.

To meet this requirement, organizations must become good learning

systems; they have to introduce improvements in their products and services, in

the processes they use to deliver value to the customer, and in the ways they

organize to carry out these processes. Organizations

are having to formulate organizing strategies for dealing with these performance

pressures (Morhman, Cohen, & Morhman, Jr., 1995)

Morhman, et al.

(1995) document that during the past three decades, an increasing number of

production settings have found that they could significantly improve their

effectiveness by establishing teams that have responsibility for a “whole”

part of the work. For the most

part, this increase reflects that teams are an appropriate structure for

implementing strategies formulated to deal with performance demands and

opportunities presented by the changing business environment (Morhman, et al.,

1995). Rayner (1993), shares that

“any organization that is considering improving its product quality,

productivity, ability to innovate, service, or employee relations has to

seriously consider these innovative work systems” (p. 4). Increasingly,

it is being recognized that the fit between strategy and organizational design

is a competitive advantage. Morhman,

et al. states, “appropriate organizational design enables an organization to

execute better, learn faster, and change more easily” (p. 7).

What is a Team?

One definition of a

“Team” defines the term as a group of individuals meeting periodically to

solve a problem, improve a process, or take advantage of an opportunity These

individuals (normally a group a five to ten people) are united by a common

purpose and typically use a common methodology to come to consensus (ODI, 1993).

Recardo, Wade,

Mention, & Jolly (1995) define a team as “a unified, interdependent,

cohesive group of people working together to achieve common objectives. Whereas

each person may have a specialized function, each person also needs the

resources and support of others and must be willing to forego individual

autonomy to the extend necessary to accomplish those objectives” (p. 6).

Characteristics

of Teams

Recardo, Wade,

Mention, & Jolly (1995) share that a successful team will have the following

characteristics:

-

Definable

membership. This means defining the

roles, responsibilities, and limits of decision-making authority of each

member. Each member must also be consciously aware of the deliverable for

which they are responsible.

-

Membership stability.

Teams must have a core of individual members who will be with the team

throughout the team’s life. This

core provides continuity.

-

Common goals.

Team members must understand the goals and objectives that they were brought

together to achieve. Team

sponsors and managers play a pivotal role in defining these goals and

objectives and communicating them to team members.

Of equal importance, the team members must think the goals are

worthwhile so they will commit to achieving them.

-

Sense of belonging.

Team members must feel that they belong to the team and are full

contributing members.

-

Interdependence.

Teams are only teams if there is a large degree of interdependence. That is, one team member’s performance is dependent upon

the inputs and outputs of other team members.

-

Interaction.

Team members must interact with each other to be considered a team.

Close proximity helps to solidify and bond team members together.

-

Common rewards.

Having common performance metrics and reward systems is essential to a

team’s long-term viability.

Self-Directed

Work Team Development over Time

Teams are

associated with a management model Ed Lawler calls high involvement, high

participation (HIHP). HIHP emerged

from sociotechnical theory, which originated in the coalmines of England during

the early 1950s. This model

suggests that increased productivity is achieved when workers are highly

involved and participate in every aspect of the work they perform (Recardo, et

al. 1996).

Through the Self-directed team approach, based on sociotechnical theory,

faded in the 1970’s, it re-emerged in many companies in the 1980s. Just-in-time (JIT) production greatly revolutionized the

factory floor in the late 1960s in Japan and did the same thing in the United

States in the late 1970s (Recardo, et al. 1996).

The quality and productivity work of W. Edward Deming, Joseph M. Juran,

and Philip Crosby have all pointed out the positive effects of involving

employees in decision-making, productivity improvement, and customer

satisfaction. However, for the last

35 years, HIHP has been largely a curiosity, not a mainstream style of

management, in spite of impressive results like the following:

-

Xerox

plants using teams have 30% higher productivity than their traditionally

structured plants.

-

Proctor

& Gamble gets 30 to 40 percent higher productivity in its team-based

plants.

-

GM reports a 30- to

40-percent increase in productivity in its self-directed, JIT plants.

Recardo, et al. (1996) identify that

the HIHP model has seven basic elements:

- Employees must be actively involved in designing

processes and structures of the organization.

This means employees must be given all the information they need to

be successful.

- Employee

manage the team, management manages the boundaries and the environment

outside the team.

- Employees

are in charge of production and services; they have the authority to start,

stop, or fix production.

- Employees

are cross trained to do several jobs and compensated for learning new

skills.

- High-quality

products and high-quality work life are inseparable.

- Continuous

process improvement must be a way of life.

- To

a greater degree than in the past, employees hire, fire, and determine pay

rates.

At

about the same time sociotechnical theory was being developed in Europe, Douglas

McGregor was beginning to wonder why traditional management systems, called the

scientific management model, didn’t work anymore (Recardo, et al. 1996).

The scientific management model focused on efficiency or time and

movement in production. In the

1970s another management model appeared called the performance management model.

This model stipulated that getting stakeholder buy-in was critical to

increased productivity. The

underlying theory in performance management is that employees need to know where

they are going, how they are going to get there, and what their roles and

responsibilities are. From this

model we now have goals and objectives in our business plans (Recardo, et al.

1996).

Benefits

of Teams

Recardo, et al. (1996) identify some

common benefits of teams as:

-

Better solutions.

A group of individuals brought together to solve a business problem is much

more likely to come up with a better solution than is an individual working

alone. The collective brainpower of a team frequently outmatches the single

brainpower of an individual.

-

Increased motivation of members.

Most managers are not trained, rewarded, or reinforced for making the

workplace a sociologically and psychologically healthy experience and

therefore misunderstand its importance in the forging of a good team.

Employees who work in teams typically state they have received more

support then they would have in a non-team environment.

In a well-run team the social interaction of team members is a

positive and rejuvenating force.

-

Increased knowledge.

Teams provide all members with connections that can lead to new

opportunities and new work experiences that would be less likely to occur in

a traditional work environment. People

are exposed to other jobs and ideas that will make them more valuable in

their own jobs.

-

Better use of resources.

In today’s increasingly competitive environment, a key source of

competitive advantage for many organizations is waste reduction.

Teams are frequently a cost-effective way of reducing resource costs

through sharing human as well as material and financial resources.

-

Increased productivity.

Teams go through a life cycle. During

the early stage3s of that life cycle, team failures are very high and very

frequent. It is not unusual for

self-directed teams to have a failure rate as high as 60 percent.

But once through that life cycle, initial productivity increased of

15 to 30 percent are common. In

organizations with a long history if implementing teams, their success rates

are much higher, and consequently productivity increases come more rapidly

and with fewer failures.

Additionally

according to the ODI, Making Teams Work (1993) handbook, there are three

prime benefits to teams:

- They

get work done.

A well-run and well-motivated team, with a clear focus and

appropriate technology, can solve problems that have remained unsolved for

years or improve processes that have been bottlenecks or major sources of

waste and rework. Through group

creativity and the synergy that comes from constructive interaction, teams

can save organizations many times what they cost in time and support.

-

They

tear down walls.

Teams span boundaries –individual boundaries, functional

boundaries, hierarchical boundaries, even the boundaries that separate the

organization from the outside world. Teams

become a catalyst that allows different parts of the organization to

interact, to learn, and to take joint action.

-

They

strengthen the organization. Teams

make an organization healthier by getting people in the habit of

communicating, taking responsibility, thinking logically, and taking action.

Through their emphasis on “management by fact,” teams ensure that

the focus is on issues and not personalities.

Kinds

of Teams

Today, teams are

configured in hundreds of different ways. All

teams fall across a conceptual continuum from those that are reactive,

tactically focused like simple problem-solving teams, to those that are more

proactive and focus on being self-supportive as in self-directed work teams.

Recardo, et al. (1996) break down teams structures into four main types

of teams.

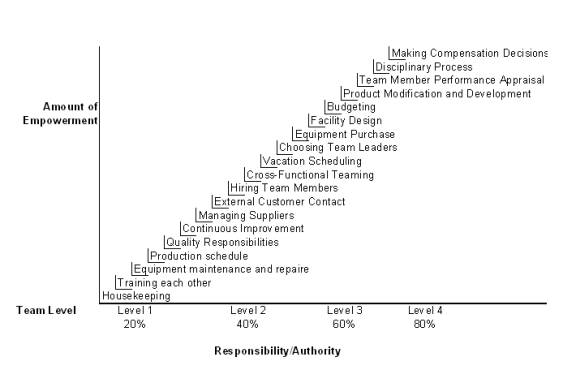

Figure

1.2, Recardo, et al., 1996 (p. 10): The Team Continuum

-

Simple Problem-Solving Teams.

Simple problem-solving teams typically address intra-unit problems over a

fixed time frame. Membership is

typically mandated, and these teams tend to be reactive and tactical.

They are typically easy to design and implement because they require

little systems integration.

-

Task Forces.

Task forces are composed of team members with highly specialized skills,

brought together from different functions across the organization for the

purpose of solving complicated problems requiring a high degree of

specialization. Task forces

usually conduct research and make recommendations but do not implement

solutions.

-

Cross-Functional Teams.

Cross-functional teams are composed of team members who are brought together

from different functions across the organization to analyze, recommend

alternatives, and solve complicated problems.

Unlike a task force, a cross-functional team implements its findings

and recommendations. Team

members are often highly skilled or specialized within their fields.

Some organizations have attempted to create permanent

cross-functional teams, but the results so far are discouraging.

The problems appear to be universal to all cross-functional teams.

They include such things as lack of personnel resources, poorly

detailed business plans, lack of clear roles and responsibilities, no clear

chain of command, and lack of sponsor support.

-

Self-Directed Work Teams.

Self-directed work teams (SDWTs)

manage their own internal affairs. More than any other team, self-directed work teams evolve

over time. They may come to

control human resource decisions (hiring, firing, compensation, vacation

scheduling, and so forth), often have budgetary and financial control,

interact with customers, decide production schedules based on business

goals, and generally have the authority to improve work methods.

Self-directed work teams are by far the most difficult type of team

to implement because of the extensive systems integration required (they

affect the information system, administrative control systems, human

resource systems, and so on), they; correspondingly, have the lowest success

rates.

When

should you Form a Team?

Part of an

organization’s success in implementing teams deals with how they chose to

implement those teams. Recardo, et

al. (1996) identify that many organizations have learned through the years that

for all the measurement done concerning teams, four measures are ultimately

important:

-

Customer

acquisition, satisfaction, and retention.

-

Increased

productivity.

-

Employee

satisfaction.

-

Improved

cash flow.

The above four

performance measures are often the major drivers for most high-performing

organizations. When investigating

whether or not teams are right for an organization, these four important

performance measures should be kept in mind.

If teams cannot positively impact these four performance measures,

chances are time and resources will be wasted implementing teams.

According to the

ODI, Making Teams Work (1993) handbook, Teams make sense under any of the

following conditions:

-

When a problem

or opportunity can benefit from concentrated attention by a group of people.

-

When

the cause or causes of a problem are unknown or uncertain.

-

When

the solution is not obvious.

-

When

functional or other interests impede the selection of the best course of

action for an organization.

-

When

consensus is necessary for organizational support or effective

implementation

Teams—one potential design element—should be adopted because they are the

best way to enact the organization’s strategy and because they fit with the

nature of the work, not because other companies are using teams and claiming

success (Morhman, et al. 1995).

When

shouldn’t You Form a Team?

The key question to ask is whether a

particular task is best accomplished by establishing teams to allow members to

integrate their activities. Teams should not be established simply because

there is a need for speed, efficiency, quality, innovation, and customer

responsiveness. They should be established because a team structure is the

best way to achieve the integration required to accomplish these strategic

goals.

Teams are not the

right choice when the conditions cited above do not exist. They also do

not make sense when you have insufficient support or insufficient time to do the

job right, or when, for security or other reasons, the information to make a

decision is not available to the team (ODI, 1993).

Teams, then,

cannot be the answer to all problems. It also is important to recognize

that decision-making frequently takes longer for a team than for an individual,

coordinating schedules is often difficult, and more viewpoints need to be

reconciled.

Recardo, et al. (1996) go on to further share that teams are not risk free.

Some of the more common risks associated with implementing teams are as follows:

-

Loss of

control. Most Americans have grown up

without working in a communal or team environment. Furthermore, the

compensation system in almost all corporations is based on rewarding the

individual and not the team. Teams make many people feel as thought

they have lost some control or freedom over their work lives, where as

employees who have worked on factory floors or in the back office are much

more likely to be at home in teams. Managers and supervisors tend to

be threatened by teams because they have to surrender some of their

traditional power to the team.

-

Imposed

consensus. With teams individuals may

not always get what they want. All of us have identified and

oftentimes offered what we think is the perfect solution to a problem; in

teams, we may discover that we are the only one who thinks this the perfect

solution. In order for teams to work, a consensus among differing

opinions must be forged and acted upon as a team.

-

Managing

multiple relationships can be difficult.

In a team composed of ten members, the effort to manage relationships is

complex.

-

Changing

roles and responsibilities. The roles and

responsibilities of managers and employees change significantly when teams

are implemented, and change is uncomfortable. Employees gain more

power to influence work and are required to assume more responsibilities and

be more proactive than in the past. Employees also tend to be held

more accountable because they and not their bosses are responsible for key

outputs. Managers because leaders instead of drill sergeants, coaches

instead of control agents. To many employees and managers this shift

in roles is disconcerting, particularly if they have not received enough

training to take on the new responsibilities.

-

Cost.

Initially, teams re expensive to implement. Increased training costs

and lost productivity can be expected. Sometimes redundant systems

must be maintained during the transition period. Human resources

systems may have3 to be redesigned, including compensation and the

performance management system.

Empowered

Teams – Creating a Structure for Support

The use of teams

and teaming mechanisms to integrate organizations laterally has increased

because many organizations, especially those that are highly complex, have found

that traditional hierarchical and functional approaches are inadequate to

address their coordination needs in a timely and cost-effective manner (Morhman,

Cohen, & Morhman, 1995).

Mohrman, Cohen, & Mohrman,

Jr. (1996) share that while performance pressures are driving many organizations

to a more lateral way of functioning, financial pressures are driving other:

they can no longer afford the costs of the burgeoning hierarchy as a means of

integrating increasingly complex work. These

costs include not only expenses resulting from proliferation of managerial and

control roles but also those resulting from the delays and lack of

responsiveness and learning that are build into an organization that is

horizontally and functionally segmented. But

teams, a likely design component of the flat, laterally oriented organization,

are not an inexpensive design either; they involve the costs of coordination

time among multiple people. For

that reason, they should be used only where they are appropriate to both the

task environment of the organization and the nature of the work to be done.

Organizations that intend to make substantial use of teams to do work, manage

and integrate work, and improve work cannot simply establish teams, train them,

and expect them to operate effectively (Morhman et al., 1995).

Rather, organizations must be designed, or redesigned to support this new

way of doing work.

Implementing

Teams

Why are so many

of today’s organizations looking to work teams?

This change is taking place because more people are realizing that

empowered teams provide a way to accomplish organizational goals and meet the

needs of our changing work force.

As plants,

hospitals, service organizations, and American businesses as a whole seek to

become more efficient, they cannot overlook the advantages offered by flexible,

self-disciplined, multi-skilled work teams.

Meanwhile, workers recognize the benefits inherent in the self-directed

work environment: and opportunity to participate, to learn different job skills,

and to feel like a valuable part of the organization.

Based on data

from a survey conducted by Wellins, Byham, & Wilson (1991), shows the top

reasons senior line managers give for their organizations; movement toward

self-directed work teams.

|

Primary

Reasons Cited for Moving Toward Self-Directed Teams

|

|

Cited as Primary Reason

|

Respondents

(%)

|

|

Quality

|

38

|

|

Productivity

|

22

|

|

Reduced operating costs

|

17

|

|

Job satisfaction

|

12

|

|

Restructuring

|

5

|

|

Other

|

6

|

|

Source: Wellins, Byham, & Wilson (1991).

|

|

Some of these and other reasons for

establishing teams are elaborated on below:

-

Improved

quality, productivity, and service. To

stay competitive, today’s organizations must bundle service, quality,

speed, and cost containment into one package.

Success in these areas seldom comes from giant leaps; rather it comes

from thousands of small steps taken by individuals at all levels in the

organization. The sense of job

ownership resulting from the team concept has led to an emphasis on

continuous improvement, which in turn has led to amazing leaps in quality,

productivity, and service.

-

Greater

flexibility. Advances in service quality today rely heavily on the

organization’s ability to discover ways of increasing its responsiveness

to customers and the marketplace. In

searching for ways to adapt more quickly, many companies are realizing the

inherent advantages of work teams. Teams

can communicate better, tackle more opportunities, find better solutions,

and implement actions more quickly. Many

teams in manufacturing environments are organized into natural work teams,

which reorganize in a fluid way to accommodate shifting demands in

production. Because of the

nature of teams, their members are often more engaged, alert, proactive,

knowledgeable, and generally better able to respond to varying conditions

than traditionally organized work forces.

-

Reduced

operating costs. To remain competitive, many companies have been forced to

eliminate layers of middle-level management and supervision.

With fewer managers, many decisions must be made at lower levels.

Empowered teams provide a vehicle for employees to take on the

responsibilities typically reserved for managers and supervisors.

-

Faster

response to technological change.

Today’s advanced manufacturing technologies call for different and

usually higher worker skills. These technologies also create closer interdependence among

activities that were once separate; thus, workers who previously worked

alone now must learn to work together.

-

Fewer,

simpler job classifications.

As technology becomes more complex and the need for flexibility

grows, many organizations see a corresponding need for multi-skilled

individuals who can perform many different job functions.

Today, employees are asked to perform several functions, often

rotating and filling in for one another.

Teams are designed to facilitate job sharing and cross-training.

-

Better

response to new worker values.

Employees today welcome autonomy, responsibility, and empowerment

that self-directed work teams provide.

The results of a recent Louis Harris poll, as reported in the Behavioral

Sciences Newsletter, show that all employees who were asked, “Do you

want the freedom to decide how to do your work?”

77 percent answered “yes.” Employees

reported that factors such as the challenge of the task, participation in

decision making and work that gives a feeling of accomplishment are more

important than high levels of pay. Those

values and “wants” are wholly consistent with the empowered team

concept.

-

Ability to

attract and retain the best people. Organizations

that acquire and retain capable work forces will offer a culture that

matches the values of the new work force.

Teams offer greater participation, challenge, and feelings of

accomplishment. Organizations

with teams will attract and retain the best people.

The others will have to do without.

An organization empowers its people when it enables employees to take on more

responsibility and to make use of what they know and learn.

For some positions, there is no limit to the amount of empowerment that

is possible through increases in job responsibilities.

This is especially true in many professional and managerial positions. In such cases, the degree of empowerment is directly

proportional to the amount of responsibility.

Increasing responsibilities yield corresponding amounts of empowerment.

Unfortunately, this relationship does not apply to the wide range of single-task

jobs designed for manufacturing and service organizations.

For individuals in these jobs, while the scope of the job may continue to

broaden, which will enhance the sense of empowerment and job ownership, at some

point, however, the empowerment curve will begin to flatten out, because there

is only so much that can be done by oneself.

In other words, amounts of empowerment and responsibility eventually stop

tracking in direct proportion to each other.

Further duties would seem less meaningful, unrealistic, or too much like

‘make-work.’ Additional tasks would no longer be feasible or desired.

Employee

and Team Responsibility

Source: Wellins, Byham, & Wilson (1991). |